Why do we prioritise availability over performance?

The average wind turbine size we monitor is approximately 2.5MW. On a 4-turbine wind farm that runs at a capacity factor of 35% we can expect about 30GWh production per year. So, the impact of stopping all 4 turbines an additional 1% of the time adds up to a loss of around £23k in revenue per year (assuming a power price of about £75/MWh).

The same amount of production is lost if the turbines are continuously operating at an average 1% lower efficiency. Although most people are aware of this, performance optimisation still doesn’t get as much attention as downtime. There are a few reasons for this:

1. Visibility: Performance issues are generally harder to spot. Metrics for site performance sometimes do include suboptimal performance, for example in a production-based availability, but even if that is the case, these metrics don’t capture small continuous changes in performance (more on this later). So, the loss is hidden from the main metrics used in the industry.

2. Urgency: If a turbine is offline an additional 1% of time in a year, it would be off for an extra 3.5 days. For our example site, this equates to losing £1575/day on average (for a short duration of 3.5 days). This same turbine continuously operating at -1% efficiency will only result in losses of about £16/day, significantly reducing the urgency, even if the total over a full year is the same. There is a risk that the lower urgency of the performance issue means it doesn’t get fixed at all.

3. Cost of resolution: The impact of dealing with the issue is also important. An unavailable turbine is already stopped, but the fix of a performance issue may require a stop of the turbine to investigate. We wouldn’t want to stop the turbine for 2 hours to investigate a low-urgency issue, on a windy day, when we could opt for letting it run sub-optimally until the next maintenance visit or low wind conditions. An optimised maintenance strategy can bring significant value, but comes with a lot of complexity like parts lead times, availability of specialized staff, site access conditions, and of course wind resource.

4. Incentive: The contractual agreements provide financial incentive to increase availability. As sites are often serviced by different parties than the owner, the availability metrics play an important role in determining the site team performance and there is therefore an incentive to keep availability high. This is less so the case for performance.

The wind industry understands availability contracts may not tell the full story and therefore often production-based availabilities are adopted. Production-based availabilities don’t just consider operation time; they also consider lost production and can capture periods of turbine derating.

However, production-based availabilities generally only include clear turbine curtailments or deviations from the normal operating power curve. This simplifies the calculation and therefore the path to agreement on a final value between different parties such as service providers and owner/operators.

Availability is a good metric to manage contracts with, and it incentivises a quick resolution of issues that significantly reduce turbine output. However, time- and production-based availability measures capture – at best – large deviations from the normal power curve and miss significant opportunities for site performance optimisation.

Visual power curve checks

A visual power curve review is also widely adopted, and can catch additional underperformance events. Although this is an improvement on just reviewing availability figures, it is important to remember the underlying wind speed distribution. As the wind speed distribution peaks at lower wind speeds, a clearly visible curtailment at higher power may have a similar impact as a minor performance degradation at all wind speed.

The power curve on the left highlights the lack of visibility of performance degradation in power curve analysis. The green dashed line shows a hard-to-spot, but significant, 2.5% reduction in partial load, compared the original power curve in orange. The yellow dotted line shows a much easier to identify curtailment to 2100kW. Loss of the two performance issues presented by the dashed and dotted lines is however the same, both resulting in approximately £13k/year loss on a single turbine.

What impacts the apparent power curve efficiency?

What causes such hard-to-spot drops in apparent power curve performance? And is this a real underperformance, or not?

Turbine control

As turbines are controlled mainly using generator speed, power, and blade pitch angle, relationships between these signals can be used to monitor consistency of turbine control. Furthermore, yaw control is an important factor to ensure the turbine is responsive to wind direction changes. Turbine control factors are relatively straightforward to monitor using readily available SCADA data.

Measurement issues

Particularly anemometer recalibrations are a large source of observed variations in the power curve. These tend not to impact turbine performance much as most (but not all) turbines do not use wind speed in control, other than for start-up/shut-down conditions in low and high wind. However, wind speed measurement consistency issues may mask other issues and can be corrected for, for example by means secondary sensors or neighbouring turbines (see also this interesting article)

Incorrect measurement of yaw alignment may result in a static yaw error. Turbine to turbine comparisons of static yaw misalignment due to measurement issues can also be monitored using 10-min SCADA data on many sites, but the success of this approach depends on the yaw control. The impact of performance can be significant, even if not clearly visible from the power curve.

Environmental conditions

Environmental conditions like air density, turbulent flow, wind shear and upflow impact the energy available across the full swept area of the rotor. These are not really losses, but will impact apparent power curve efficiency measures and are important to consider as a potential cause of deviation. Such drops in efficiency can often be explained by finding a correlation with things like wind direction, time of day, air density, turbulence intensity or atmospheric stability.

Rotor aerodynamics

Changes to the rotor, including loss of blade furniture, blade upgrades and/or blade degradation impact aerodynamic efficiency of the rotor. These issues tend to be a slow change over time, not identifiable in the data other than in efficiency. Therefore, if a change in efficiency is observed, wind speed calibration is corrected for/ruled out, and no other of the previous issues can be found, an on-site inspection to verify the status of the blades may be beneficial.

The cost of control issues & value of further monitoring

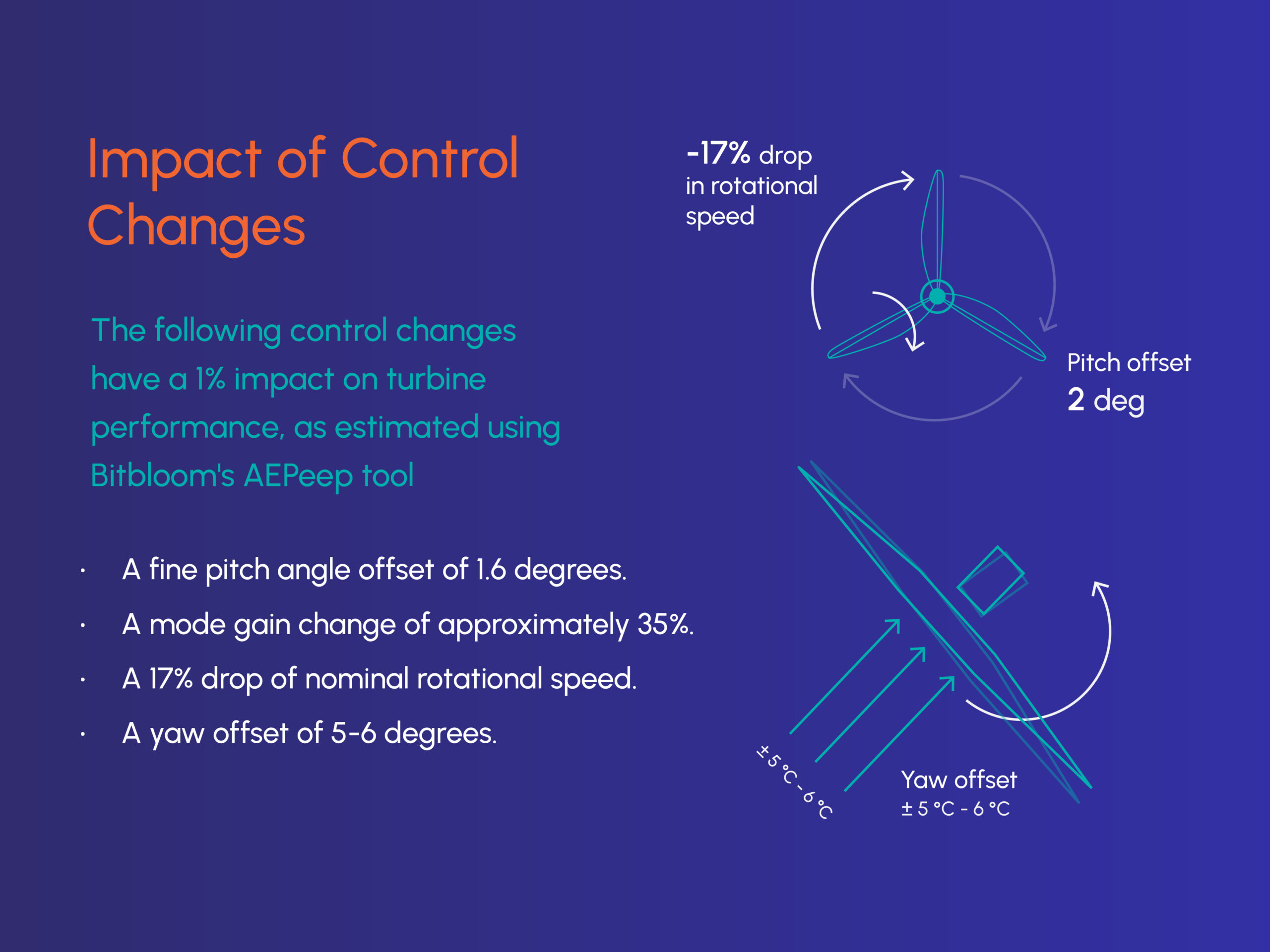

Let’s go back to our first example of a site with 4 turbines, each rated at 2.5MW. We saw an impact of 1% on the full site was roughly translated to a production loss of £23k. We used Bitbloom’s AEPeep tool to find control changes that would cause such a change in performance:

- A fine pitch angle offset of 1.6 degrees.

- A mode gain change of approximately 35%.

- A 17% drop of nominal rotational speed.

- A yaw offset of 5-6 degrees.

Besides turbine control metrics that directly impact performance, monitoring of component health (e.g., component temperatures, vibrations and long-term duty metrics) and adherence to regulatory requirements (e.g., curtailment strategies like noise modes/wildlife curtailments) can clearly provide further value, though it is harder to quantify avoided loss for these issues.

Monitoring common performance issues

Availability is understandably an important metric of site performance. But why stop there when other common performance issues with similar impacts are easily tracked, by simply utilizing readily available SCADA data?

Bitbloom’s Sift Monitor includes a lot of the performance analytics mentioned above, augmenting the more basic availability analysis found in some second layer SCADA systems. For a 4 x 2.5 MW machine site, Sift Monitor is currently £550/year, a fraction of the potential gains unlocked by performance monitoring.